The Return of Sky Ferreira

Silenced for a decade, Ferreira's awaited return to music places her in the pantheon of thwarted women artists.

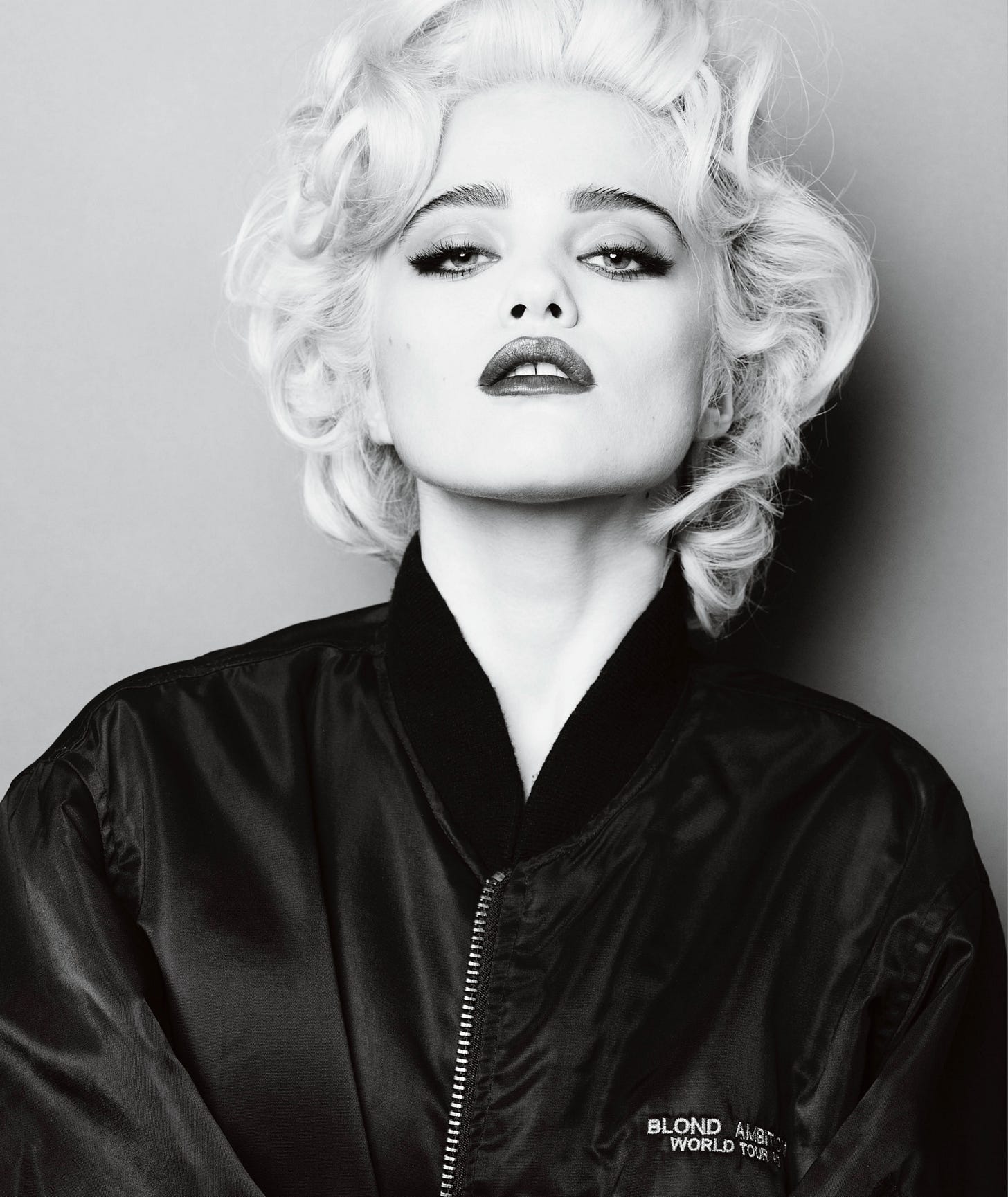

Sky Ferreira by Mario Testino for V Magazine

I recently attended an early screening of the new A24 erotic thriller Babygirl, directed by Halina Reijn. It was emblematic of Reijn’s supernova of a film—smart, subversive, and cool—that the final shot ends with the sudden burst of heavy guitars and the screech of synths before the smoky, unmistakable vocals of Sky Ferreira appear from the haze, strained and angry and urgent. The song, ‘Leash’, marks Ferreira’s first release in two years, and her first release as a newly independent recording artist. For a certain kind of person, a new Sky Ferreira song is a thing worth noting, even celebrating. Ferreira’s output since the release of her seminal debut, Night Time, My Time, more than a decade ago, has been sporadic, a litany of stop-starts, promised release dates that came and went, and alleged tours that never quite took off—a long, protracted, rarely punctuated silence. In the press, Ferreira has been cast as a reluctant pop star, an enigmatic perfectionist, even a recluse. The real narrative is less glamorous, more banal, and more worthy of attention: an artist thwarted by a foreboding, unmovable corporate machine. A so-called renaissance, marked by all the usual markers—the A24 connection, an interview in Vogue, rumblings of an imminent album release—is teetering on the horizon. On Twitter, Ferreira’s music has been circulating again. A recent post re-sharing the music video for her 2012 hit, ‘Everything is Embarrassing’, with the caption “It’s time to admit this is one of the best songs ever” was viewed half a million times.

Re-listening to Night Time, My Time is like stepping into a time machine. It’s an experience that transcends bog-standard nostalgia and feels a little like recapturing some lost version of yourself. The record was released on October 29th, 2013. A week earlier, Kanye West had proposed to Kim Kardashian at a stadium in San Francisco. A month earlier, Breaking Bad had ended, Walter White dead on the floor, Badfinger in the background. This was the year Miley Cyrus twerked at the VMAs, the year Jennifer Lawrence fell at the Oscars, the year of Beyoncé by Beyoncé, of the Harlem Shake and House of Cards and the Red Wedding. It was the year I turned 20. I was living in Sydney’s Inner West, half-heartedly attending university, and working part time at an old movie theatre on King Street. I spent my weekends partying harder than I have partied before or since, those being the halcyon days where you could take ecstasy and ride the velvet cloud of euphoria without suffering the days-long, soul-crippling comedown. I was in love with someone different every day, each crush an interchangeable avatar in a vast, vague narrative of all-encompassing romance that occupied most of my waking hours. I spent my measly cinema earnings on cigarettes, jugs of cheap beer, and, when budget allowed, spandex outfits from American Apparel. On Thursday nights my friends and I went to World Bar in King’s Cross for Propaganda, an indie-club night imported from Bristol, where we danced to Joy Division and The Strokes until we got kicked out at 6AM, when the sun was beginning to rise. The greatest sign of social cachet then was being photographed by the club photographer, who uploaded the pictures to a Facebook album the following afternoon. Images of ourselves felt completely, gloriously out of our control - a thing that happened to us, not something we proactively created.

Sky Ferreira was our girl, and long before we knew her as a musician, we knew her as an image—the Jane Birkin of the Tumblr era, a stand-in for all our aesthetic aspirations: the peroxide shag of hair, the pouting cherry-lacquered lips, that doe-eyed, kohl-lined stare, and the leather jackets, the denim cut-offs, the Raybans, the towering patent leather stilettos. Dana Boulos, the fashion photographer and filmmaker, was at the heart of this cultural moment and created some of the era’s most memorable imagery. She and Ferreira first met in 2007 at the legendary Dim Mak party nights, hosted by Steve Aoki at the Cinespace in Hollywood. “We quickly became friends since we were always the youngest at all the events during the indie sleaze era,” Boulos told me. “I’d often run into Sky at Cory [Kennedy]’s yard sales.” Boulos, who was building a name for herself as a photographer during the embryonic days of Tumblr while working as a casting agent at American Apparel, started using Ferreira in her shoots. “I saw Sky as such a muse. Her energy was magnetic at such a young age. I wanted to cast her in every project I could.” The images Boulos and Ferreira captured at that time—soft, delicate and dream-like, with a brooding darkness, lurking just beneath the manicured surface—helped shape the taste of a whole generation of young women. Boulos’ work—influenced by Sofia Coppola, Tracey Emin, and Cookie Mueller—gave us, boys and girls who felt a million miles away in Sydney, a blueprint for a different kind of creative living. “I wanted to create images that would last forever, something timeless and classic,” says Boulos. “We were deeply inspired by girlhood, capturing that energy and sharing it through the images we created. There was such a sense of freedom then.”

Sky Ferreira by Dana Boulos

With Night Time, My Time, Ferreira seemed to bottle that sense of freedom, distilling it with a witch-like proficiency into sound. The album landed with a triumphant thud. Pitchfork gave it a glowing 8.1 and heralded it “one of the most cohesive pieces of pop-rock” of the year, and everyone from The Guardian to Rolling Stone listed it as one of the years’ best albums. Having enlisted the big gun producing trio of Ariel Rechtshaid (whose Midas touch would later brush Haim, Solange, Charli XCX, and Kelela), Justin Raisen (Kim Gordon, Lil Yachty), and Dan Nigro (Chappell Roan, Caroline Polachek, Olivia Rodrigo), Ferreira created a record that blended the best elements of 80s synth and 90s grunge, punctuated by searching, introspective lyrics that elevated the standard fare of life as a 20-something, the romantic pining, the self-doubt and self-loathing. The album revealed both a sonic and aesthetic sophistication that transcended much of the saccharine, cutesy pop that was being produced at the time. A successful pop star understands the language of aesthetics as acutely as they understand sound, and Ferreira, buoyed by her work as a model, mastered the art of album visuals. Night Time, My Time’s cover was a controversial shot of a naked, water-soaked Ferreira in the shower of a Parisian hotel, smudged lipstick, a vacant downcast stare, lensed by French cinema’s enfant terribles Gaspar Noé. Her music videos, most directed by Grant Singer, looked more like the Hedi Slimane-lensed fashion campaigns than they did traditional music videos, all artful Los Angeles dreamscapes and high fashion gloss, peppered with David Lynch references. While Miley Cyrus was working with Terry Richardson to use the style of counter-culture to try and slough off layers of Disney sheen, Ferreira achieved Cyrus' desired sense of cool with unaffected ease.

Night Time, My Time landed at a specific moment in time. The same week Ferreira’s record came out, I saw a 16-year-old Lorde—shy, awkward, and already dazzlingly brilliant—play her new album, Pure Heroine, in full to a few hundred people at Sydney’s Metro Theatre. Listening back now, what both Night Time, My Time, and Pure Heroine captured was a portrait of youthful reverie and anxiety that was entirely unburdened by the homogenous tedium that marks life on social media in 2024. Lorde’s insecurities were fuelled by MTV music videos of rap artists; Ferreira’s by magazine covers and tabloid news. There’s something deeply, romantically juvenile about the way both artists discuss self-perception, vulnerability, and romance. In ‘Boys’, the opening track on Night Time, My Time, Ferreira swoons “you put my faith back in boys”. In the bridge she chants “cross my heart and hope to die, stick a needle in my eye”. In ‘Ribs’, Lorde deadpans “My mom and dad let me stay home, it feels so scary getting old.” These were artists who spent a lot of time on the internet, on MySpace, and definitely Tumblr, but they weren’t yet affected by the constant voyeurism and exhausting performative identity games of apps like Instagram. In retrospect, you feel it in the music, which has a kind of palpable expansiveness to it, a physical spaciousness. It’s as if you can hear that Ferreira and Lorde spend their days in cars driving down highways, in the wide open cities of Los Angeles and Auckland. Life feels vast, careening, full of possibility.

When I look back now, I think of 2013 as the final year of something. It’s a fact I have always chalked up to meeting my husband in 2014, when life fell into a sort of ‘Before Zach/After Zach’ paradigm. Looking back, I don’t think this is entirely accurate. 2013 feels so much further away than 2014, in part because 2013 was the dying sigh of an era that predated the full proliferation of social media. In the winter of 2013 I travelled with two friends around Europe, to Berlin and Prague and Budapest and Paris. I know I had an Instagram account then, but I remember my main priority was taking artful pictures of rivers and nightclubs and the clothing in flea markets on a digital camera. Once a week, I’d edit the pictures and upload them to a blog. By the time I met Zach in California the following summer, I was almost exclusively taking pictures on my iPhone and posting them to Instagram. When we visited the Elliot Smith memorial in Silver Lake, I made Zach take a picture of me standing against the painted mural and uploaded it to Instagram while we were having coffee half an hour later. It was embarrassing, but I got hundreds of likes, and this gratification far outweighed the fear that a new romantic paramour might find me lame, an obscenely high threshold to cross and a testament to how immediate the opiate-like pull of digital approval really was.

In the decade since, as we all migrated onto the internet full time, life has started to feel claustrophobic and small, and pop music has largely adopted this sensibility. Compare the lyrics on Night Time, My Time and Pure Heroine with the lyrics on any of the major pop albums that came out this year. The first thing you encounter is a wall of mirrors, a kind of dizzying, nauseating funhouse. “When you’re in the mirror, you’re just looking at me”, declares Charli XCX on ‘360’. “I’m dancing in my own reflection”, Addison Rae coos on ‘Aquamarine’. “She’s in the mirror taking pictures”, Billie Eilish sighs on ‘Lunch’. There’s also a lot of talk of cages. Billie Eilish is “stuck inside a bird cage”, 21 and wondering if she’s still relevant. Taylor Swift sings that “people only raise you to cage you”, and “this cage was once just fine”. Some things never change—love, the having and losing of it, the intricacies of female friendship and jealousy—but now everyone is also obsessed with outside perception, with what people are saying about them, whether or not people like them. Everything is internalised, self-absorbed, referential. It’s a culture of pre-empting critique, getting in on the joke before anyone else can make it at your expense. In ‘But Daddy I Love Him’, Swift grieves that she can’t be with the man she loves because “judgemental creeps” on the internet have turned on her (she resents it, but there’s no question that she’ll kowtow to them). Ariana Grande is more explicit: “why do you care so much whose dick I ride?” she asks in ‘Yes, And?’ Charli XCX makes constant references to, well, references. “I’m your favourite reference baby”, “It’s okay to admit that you’re obsessed with me”, “It’s so obvious I’m your number one”. Where pop once indulged in a sense of infinite possibility, there is now only a heavy, exhausting self-awareness. If we once looked optimistically outward, we now look endlessly inward.

Sky Ferreira signed with Capitol Records in 2009 when she was only 17 years old. In her telling, the cracks started to appear from the get-go, as they tried to mould her into “Britney Spears-meets-Lolita”, a kind of proto Katy Perry. The label’s plans for Ferreira are laid bare in her early singles ‘One’ and ‘Obsession’, soulless, forgettable pop fare in which Ferreira, weighed down with bad hair extensions, was forced to writhe around purring “I want to be your obsession” (a signal that creative tensions were already afoot, the music video for ‘Obsession’ was, at Ferreria’s request, a bizarre love story about a teenage girl obsessed with the Reservoir Dogs actor Michael Madsen). For years Ferreira reportedly worked on “more than 400 songs” with Capitol, all discarded, before going rogue and writing and recording her own music. The fruits of her labour culminated with 2012’s ‘Everything is Embarrassing’, co-written and co-produced by Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes. The chasmic difference between ‘Obsession’ and ‘Everything is Embarrassing’, recorded only 18 months apart, showcases how much more evolved a young Ferreira’s tastes were than the team at her label. ‘Everything is Embarrassing’ announced Ferreira as a serious artist. It’s one of the best pop songs of the 2010s, an 80s-tinged synth daydream weighed down with a palpable, hypnotic sadness. Ferreria’s confidence as a writer and performer are remarkably assured. Does anything capture the nihilistic uselessness of unrequited young love like her wistful refrain in the chorus: “I’ve been hating everything, everything that could have been, could have been my anything, now everything’s embarrassing”?

Capitol were reluctant to release ‘Everything is Embarrassing’ and by the following year, when Ferreira entered the studio with Rechstaid, Raisen and Nigro to record Night Time, My Time, communications had broken down so badly that she had to self-fund the recording sessions with money made from her modelling work. "That was the entire fight: I wasn't going to be what they wanted me to be because I couldn't do what they wanted me to do," Ferreira told Pitchfork when the album was released. Ferreira alleges that in the years since—perhaps as retribution that they were proved wrong in such spectacular, public fashion by a 21-year-old girl—Capitol have stalled her career using “blatant sabotage”, refusing to fund recording sessions, undercutting publicity opportunities, and indefinitely delaying the release of a follow-up album (the perhaps aptly named Masochism), a process known in the industry as “greylisting”. It’s clear that the emotional impact of this decade of chaos and uncertainty has been significant for Ferreira. In ‘Leash’, Ferreira’s song for Babygirl, she sings about a sado-masochistic relationship between two parties. “Surrender to the master, in the end nothing matters,” she wails in the chorus. At first glance one would think this was in reference to the film's plot, Nicole Kidman plays a sexually repressed CEO who embarks on a complex affair with a much younger intern, played by Harris Dickinson. But it’s clear that the lyrics are also about Ferreira’s toxic relationship with her own record label: “Chains are heavy, pull me close to you, every scrape leads me back to you.” Speaking to Laura Snapes in The Guardian in 2022, Ferreira spoke of her relationship with Capitol in abusive terms: “I felt I was gagged and bound,” she said. “You have literally ruined my life. My life was taken from me. It’s literally me. It was like literally being in solitary confinement.” In late 2023, Capitol unceremoniously dumped her via e-mail, a freedom of sorts, but she speaks a lot now about lost time. “I’ve had to accept that I’m not getting those 10 years of my life back” she said in an interview with Vogue this month, echoing the sentiment in IndieWire: “That was literally half of my life. In the last year, I’ve really been trying to figure out how to go about this and rebuild all this, but I’m also angry that I have to begin with, because it wasn't fair.”

This is nothing new. The history of music is lined with artists who were thwarted, undermined and otherwise mistreated by moneymen who fed on their creative genius like leeches only to carelessly discard them. This happens to artists regardless of gender—Prince famously began writing ‘slave’ on his cheek during live performances to protest the conditions of his contract with Warner. Frank Ocean released debut mixtape, Nostalgia, Ultra, independently because Def Jam shelved it (he eventually got back at them by releasing his masterpiece, Blonde, independently, the day after he released his final contractually obligated album for Def Jam, the forgotten visual album Endless). But the tactics used to discredit female artists—accusing them of being crazy, or drug-addicted, or unreliable—have, historically, had a uniquely silencing impact on women. Ferreira is often compared to Courtney Love and Sharon Manson, but more apt comparisons might be Kate Bush and Fiona Apple, artists whose early work was almost buried by recording labels desperate to dumb down their output and sexualise their nascent womanhood. Bush famously fought with EMI to release ‘Wuthering Heights’ as her first single, and resented being rushed to release a subpar follow-up album only nine months after meteoric success of The Kick Inside. She eventually launched a recording label and built her own studio to assert her creative independence, but was quickly branded, in Bush’s own words, a “weirdo recluse”, plagued by rumours that her stretches of silence were due to a nervous breakdown.

The Fiona Apple/Sky Ferreira comparisons are even more prescient. Both grew up in American coastal cities in the proximity of artistic greatness (Apple’s parents met on Broadway, Ferreria’s grandmother was Michael Jackson’s hairdresser and she spent weekends at Neverland). Both artists were signed with major labels as 17-year-olds, Apple with Sony, Ferreira with Capitol. Both women experienced meteoric success with their debut albums. Both found themselves at the centre of drug scandals. Both have undergone long stretches without releasing any music, which created a chasm for rampant and often unkind speculation about their emotional wellbeing. Like Apple, Ferreira is an artist whose artistic credibility has been obscured by a salivating obsession with her beauty. The controversy around Ferreria’s Noé-lensed album cover calls to mind the backlash against Apple’s music video for ‘Criminal’. Young female stars need to be sexy, but God forbid they embrace that sexuality unabashedly, or they’ll be destroyed in the press. “I had to be this wholesome teenager from Los Angeles, but sexy as well, but in a weird way because I was underage,” Ferreira told The Guardian in 2013. “You can be sexual if it benefits them, but if it benefits you, then forget it.” In a 2012 interview with Rookie, she likened her early experience with music producers to being “whored around”. This echoes a quote from Apple, speaking to The Washington Post in 1999 about the media: "They screwed me from the beginning.”

The reality of this power dynamic—young woman versus the large, masculine machine seeking to dominate her—takes on a more sinister tenor when one considers that a major theme in the work of both Ferreira and Apple is unpacking and addressing of the trauma of childhood sexual abuse. It’s not a coincidence that Ferreira took the album title Night Time, My Time from a line spoken by Laura Palmer in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. Palmer is perhaps the most heartbreaking of all the abused girls in the history of cinema. In one of that album’s most popular tracks, ‘I Blame Myself’, the poppy melody obscures lyrics about disassociation, self-disgust, and self-blame. “How could you know what it feels like to fight the hounds of hell?” Ferreira asks. “I just want you to realise I blame myself.” Apple’s work is littered with allusions to sexual violence, and she has spoken openly about being assaulted as a child. In 2020’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters, one blazing, unforgettable line goes: “Good mornin’ Good mornin’ You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.” There’s a grotesque irony that music and art became Ferreira and Apple’s salvation from their pain, and that the sordid machinations of industry turned that sanctuary into another kind of prison. To stop an artist from making and sharing their art is more than capitalistic cynicism, it’s what the psychologist Jonathan Shay calls “moral injury”. The violation of one’s deeply held beliefs—or perhaps, their ability to express themselves through their art—can lead to depression, anxiety, spiritual and existential crises, social withdrawal, and strained interpersonal relationships. Both Sky Ferreira and Fiona Apple’s fans have seen and rallied against the injustice of their treatment by the music industry. In 2006, when Sony shelved Apple’s third album Extraordinary Machine out of fears it was too experimental, fans launched a “Free Fiona” campaign, which eventually led to the album’s release to near-universal critical acclaim. Last September, Ferreria’s fans launched a similar campaign, even paying for a plane to fly a banner with the words “Free Sky Ferreira” over the Capitol Records building in Downtown LA.

They listened, releasing her from her contract shortly after. But there are tangible obstacles that come from a public falling out of that magnitude. "I have this reputation from 'insiders' for being difficult,” Ferreira told Interview in 2022. “But people only considered me difficult because I wouldn't just agree with everything they said. Like, 50-year-old men telling me how to be a woman!” It’s a trope so tired it borders parody, (cue also: Sinead O’Connor, Amy Winehouse, Britney Spears, Bjork, Lauryn Hill, Alanis Morisette, Ke$ha, Courtney Love, Solange… in fact, it’s harder to find a reputable female artist who wasn’t chastised for being “crazy” than it was to find one who is), and a tactic used by patriarchal systems of power since the dawn of recorded time (see also: the burning of witches, the Victorian hysteria panic, and the systemic blacklisting of outspoken Hollywood starlets). Speaking to Vogue, Ferreira said she fears that, despite being released from her contract, she still won’t be able to work. “[Capitol] made it look like I’m a lost cause, so that by the time I was free, no one would want to work with me.” One hopes that, on this front, the comparisons to Fiona Apple might act as a kind of premonition. Apple is 15 years older than Sky Ferreira. Today, she comes across as an artist at peace with herself, making the best music of her career. 2020’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters, which took Apple a decade to finish, was nothing short of a masterpiece. It took its name from a line in The Fall, the Gillian Anderson-helmed TV crime drama. Anderson yells out “fetch the bolt cutters” when she finds a locked room where a missing girl is being held and tortured. In the album’s title track, the one to break Apple out of her prison isn’t a well-dressed British detective, but Apple herself. “I’m ashamed of what they did to me, what I let get done,” she says. “Fetch the bolt cutters, I’ve been in here too long”. Ferreira has been working on music for the past decade, including tracks for Masochism, which she told Vogue would be released in 2025. Back in 2018, promising the imminent release of the new record, she made a rambling post on Instagram. “Despite all the infinite setbacks… I can say 10000 percent say with certainty that [Masochism] will not be compromised. Live/learn, succeed/fail, fly/burn, is fine either way as long as I’m the one responsible for it.” The music will come when it’s ready, but one only hopes that one of our generation's most deeply misunderstood artists will now be able to create with the freedom she deserves.

Wow! What a piece of writing and what an important topic. Thank-you!

An extraordinary piece, Grace. I've been looking forward to it for weeks since you touched on it on AWD. Pulling the veil back on how messed up the music industry is cannot come quickly enough.